In the spring of 2023, a recent retiree was drawn into what would become a horrifically expensive “relationship.” Lured through a dating application by someone who claimed to live in his area, he was eventually convinced to “invest” in what he was told was a safe, sure bet—something called “digital currency mining .” He would eventually invest over $20,000 in the scheme, depleting his personal retirement savings.

The scam was a new variant on what has become perhaps the fastest growing segment of online fraud, accounting for billions of dollars in losses from thousands of victims in the US alone—cryptocurrency-based investment fraud. Because of the ease with which cryptocurrency ignores borders and enables multinational crime rings to quickly obtain and launder funds, and because of widespread confusion about how cryptocurrency functions, a wide range of internet-based scams have focused on convincing victims to convert their personal savings to crypto—and then steal it from them.

Among these sorts of organized criminal activities, none seem as pervasive as sha zhu pan (“pig butchering”, 杀猪盘)—a scam pattern upon which the crime perpetrated against this victim, “Frank,” was based. Originating in China at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, pig butchering scams have expanded globally ever since, becoming a multi-billion-dollar fraud phenomenon. These scams have done more than steal cryptocurrency; they have robbed people of their life savings, and in one reported case a scam led to the failure of a small bank by ensnaring a bank officer.

In the past year, while well-worn versions of these scams persist, we’ve seen the growth of a much more sophisticated version—one that uses the power of the blockchain itself to bypass most of the defenses provided by mobile device vendors and give the scam operators direct control over funds victims convert into cryptocurrency. These new scams, using fraudulent decentralized finance (DeFi) applications, are an evolution of the “liquidity mining” scams we uncovered in 2022 marrying the script for fake romance and friendship perfected by past pig butchering operations with smart contracts and mobile crypto wallets.

These hybrid “DeFi Savings” scams overcome a number of the stumbling blocks of earlier pig butchering scams from a technical perspective:

- They do not require the installation of a customized mobile app onto the victim’s mobile device. Some versions of pig butchering apps required convincing targets to go through complicated steps to install an application, or to slip applications past Apple and Google application store review so they could be directly installed. DeFi scams use trusted applications from relatively well-known developers, and only require the victim to load a web page from within that application.

- They do not require crypto funds to be deposited into a wallet controlled by them, or wire a deposit to them, so the victim has the illusion of having full control over their funds. Until the moment that the trap is sprung, the victims’ cryptocurrency deposits are visible in their wallets’ balances, and the scammers even add additional cryptocurrency tokens to their accounts to create the illusion of profit.

- They conceal the wallet network that launders stolen crypto behind a contract wallet—an address that is given control over the victims’ wallets when the victims “join” the scam.

Special delivery

In 2020 we saw pig butchering scammers start using Apple iOS and Android applications as part of their scams, using a number of techniques to bypass app store review—including the use of mobile device profiles to distribute actual iOS apps and web shortcuts with ad-hoc deployment tools typically used for beta testers, small groups and enterprises.

In 2022 we found that the scammers were able to place applications into the Apple App Store and Google Play Store, bypassing application security reviews by changing remotely-retrieved content to load new malicious content. This made it much easier to manipulate victims into downloading the app, as it didn’t require steps such as installing a device profile or enrolling in mobile device management. But the app listings in the stores still could raise suspicions.

Earlier in 2022, we saw the emergence of a new scam pattern: the fake liquidity mining pool. These scams were initially driven mostly by social media spam groups and Telegram channels, with little in the way of the long-game confidence building done by pig butchering rings.

Instead they focused on selling the scam itself—based on a complicated “real” DeFi passive investment scheme conceptually similar to brokerage money market accounts in traditional finance but executed through smart contracts with an automated cryptocurrency exchange.

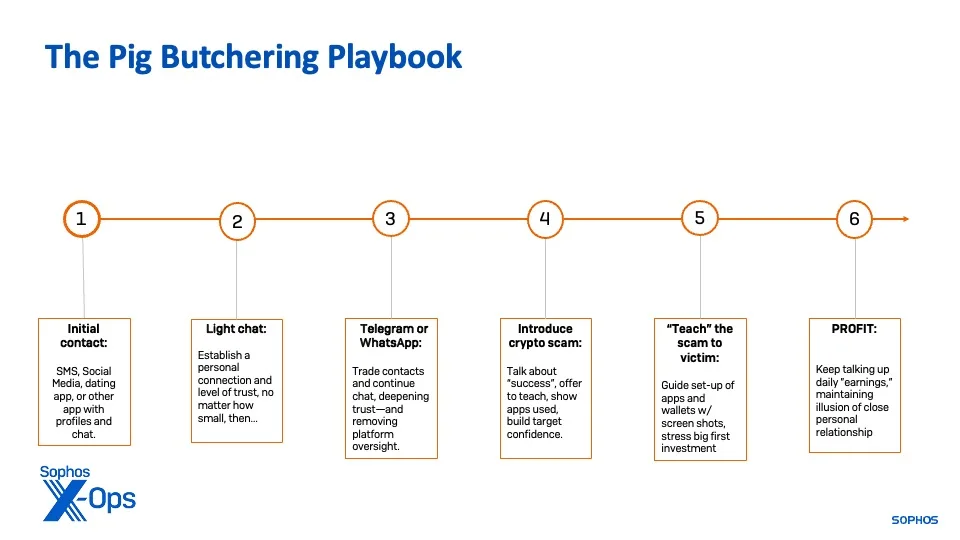

We were in the midst of follow-up research on these liquidity mining scams when we were approached by a victim of a new version of them. The criminal organizations behind the scam “Frank” and hundreds like him fell victim to use the same sorts of tactics they’ve honed with earlier pig butchering models to lure victims in—targeting primarily the lonely and vulnerable through dating-related mobile applications and websites as well as other social media.

Organization

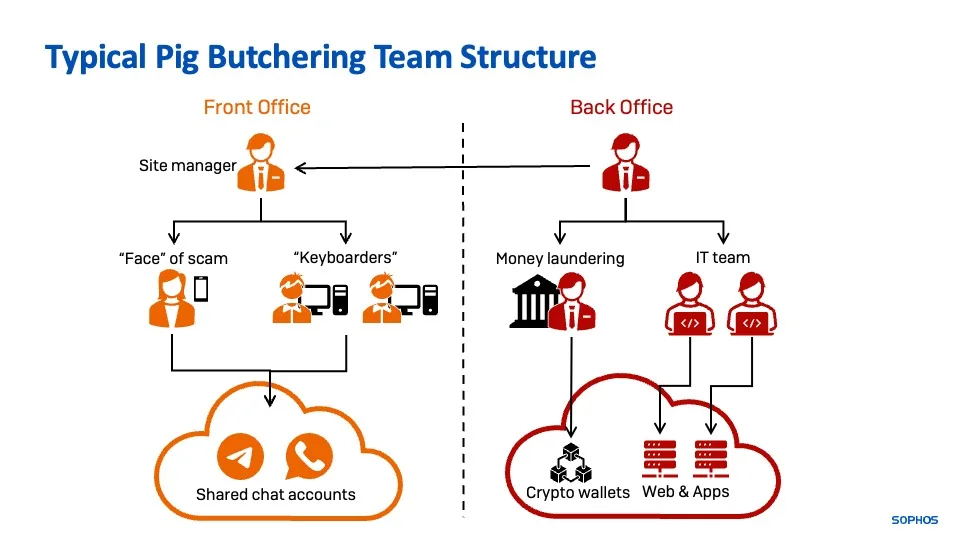

Depending on the organization behind the scam, pig butchering style organizations are broken into distinct parts, with distinct sets of tools. There is a “front office” (the “customer” facing operation that lures, engages and instructs victims) and a “back office” (IT operations, software development, money laundering and accounting). These operations may be co-located geographically, but they are often widely dispersed, with the back office team spread out internationally.

The front office operates teams of “keyboarders”—often people lured from China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia, and other Asian countries with the promise of high-paying tech or phone center jobs—to engage potential targets. They operate from scripts and instruction from their handlers, texting and sending images to targets to convince them that they are “friends” or romantically interested in the targets. In some cases, a young man or woman will act as the “face” of the scam, and engage in scheduled video calls with victims; in others, the “face” is wholly fabricated from purchased, stolen, or AI generated media.

Victims will often experience continued harassment by the scammers after they disengage, in an effort to pull them back in for further swindling. Sometimes they use information collected by the victim to contact them via other means—including text messages, emails and contact on other social media platforms—in the guise of crypto application technical support, cryptocurrency “recovery specialists,” or the abandoned “lover.”

The back office handles logistical requirements such as Internet infrastructure, domain registration, fraudulent application acquisition or development, and configuring the money laundering process.

The butcher’s toolkit

Front office infrastructure requirements include:

Mobile devices

These are typically registered with a prepaid wireless account, or are configured with an Internet Voice over IP and texting service in order to be registered with messaging platforms.

Secure messaging applications

WhatsApp is the preferred platform for targets outside China. Telegram is also used, as is Skype. Accounts registered with one device will often be shared across multiple other devices (such as PCs) so that line workers (“keyboarders”) can engage the victim in shifts.

Social media and dating profiles

More sophisticated scams use stolen or fraudulent accounts on Facebook and LinkedIn edited to support their backstory. Both social and dating profiles may use photos and videos of a designated spokesperson (often heavily edited), stolen images and videos from other accounts and platforms, or generative AI images.

A VPN connection

While some scam rings have not bothered disguising the source of their Internet traffic, others have used private VPN services to prevent geolocation.

A cryptocurrency wallet: this is used to demonstrate how to connect to the scam, and to create confidence in the target that the scheme is legitimate.

Generative AI

We have seen the increased use of ChatGPT or other large language model (LLM) generative AI to create text messages to be sent to targets. LLMs are used by keyboarders to make their conversation in the target’s language appear to be more fluent, and as a time-saving device. In Frank’s case, AI was used to write a plea for him to re-engage with the scammers in the form of a love letter after he blocked them on WhatsApp, sent via Telegram.

Back office infrastructure varies based on the scam. With DeFi mining scams, the requirements are a bit more streamlined than with scams based on fake crypto trading or other trading apps, as there’s no need for application distribution beyond the set-up of malicious DeFi sites.

Web hosting

Across all types of scams, this is usually through a reseller for a major cloud service provider—Alibaba, Huawei Clouds, Amazon CloudFront, Google, and others—and often put behind Cloudflare’s content delivery network.

Domains

Registered through Chinese or US low-cost domain registrars, or in some cases through Amazon Registry via a partner. Domain names usually include a cryptocurrency related term or brand (DeFi, USDT, ETH, Trust, Binance, etc), and one or two may be combined along with randomly created or incremented numbers and text when multiples are being created.

DeFi app kit

A JavaScript-powered web page using “Web 3.0” programming interfaces to connect to wallets via the Ethereum blockchain. Most of the fake DeFi apps we’ve examined use the React user interface library, and many are bundled with in-app chat applications that allow the scammers to act as “technical support” for the target. This kit may be organically developed by the crime ring or obtained through underground markets. The same kit can be easily set up across hundreds of domains; we found several hundred instances of the kits shown below hosted on varying services and with different domain registrars.

Cryptocurrency nodes

These Ethereum blockchain applications can reside in the cloud or on a locally-controlled computer operated by the scammers. They act as the “contract wallet” that victims form a smart contract with, and execute the transactions that reassign cryptocurrency tokens from the victim’s wallet address to the scammers’ wallets for laundering.

Destination and cashout wallets

Destination wallets are usually “offline” wallet addresses that act as a waypoint for cryptocurrency tokens to be moved to by the scammers. The stolen crypto is then usually shifted to an account on a crypto exchange—in some cases, a compromised account or one set up with false identifying information—and then cashed out. Stolen crypto may be moved through several intermediate wallets and spread out across multiple exchange accounts in an attempt to evade tracing.

Bank accounts

The final phase of the money laundering from these scams is a cashout from a crypto exchange to a scammer-controlled bank account. In the scams we tracked, the destination was a bank in Hong Kong. These are often associated with shell companies to further obscure the trail of transactions; a recent US Secret Service case found that a ring partially based in the US used a combination of US and overseas bank accounts connected to shell companies to launder $80 million.

Further evolution

Throughout our investigation of the latest DeFi mining scams and other pig butchering scams, we have seen increasing technical sophistication—much of it aimed at preventing analysis of the schemes or avoiding wallet platforms that have banned previous scams.

“Invitation codes” were an early version of this, requiring target interaction with the scammers to gain access to the scam DeFi application. More recent steps include:

- Use of agent detection scripts to block or redirect desktop and mobile browsers not associated with cryptocurrency wallets to evade analysis, and to restrict connections to specific (vulnerable) mobile wallet apps.

- Use of “WalletConnect” or other third-party APIs to obscure the contract wallet address used by the scheme

- Detection of wallet balances to prevent empty Ethereum wallets from connecting and detecting the contract wallet address

We expect that DeFi mining scams will constitute an increasing percentage of pig-butchering scams going forward because they can more easily be bundled for sale and distribution to other cybercriminals, and because they can be easily adopted by existing romance scam operators. That expectation is based on the hundreds of copies of some kits we have observed operating in the wild, and their adoption by cybercriminals in other regions.

Because these scams use legitimate software and frequently change their web hosting and cryptocurrency addresses, they often only detected once they have begun—often by banks and cryptocurrency brokerages who are alerted by large volumes of transactions from customers who have never traded in cryptocurrency before that trip money laundering and bank fraud alerts. We continue to actively hunt for the sites hosting these scams and alert mobile device makers, wallet application developers and cryptocurrency exchanges, but the scale of these scams makes it impossible to defend against all of them.

The best defense against them continues to be public education. The Cybercrime Support Network offers educational material on romance scams and investment scams that can help people spot lures for pig-butchering style crime. But reaching the people most potentially vulnerable to these scams may require a more personal touch—from friends, family, and acquaintances they trust.

More in-depth information on what we’ve uncovered about DeFi scams and other pig butchering scams can be found on our Sha Zhu Pan research page.